Last Thursday, November 20th, I was invited to participate on a podcast, Poet Talk, hosted by Ellen Miller-Mack and Meredith Foley. The show began with me reading W.S. Merwin’s poem, “Thanks”–which is a provocative beginning to the Holidays coming up–and to the conversation and reading that followed:

Author: Brad Crenshaw

Non-Stop Flights

The following book review was originally published in North American Review, October 20, 2025. Here is the link: https://northamericanreview.org/open-space/2025/brad-crenshaw/nonstop-flights-review-flight-meaning-stephen-haven

And here is the review:

Nonstop Flights: Review of The Flight from Meaning by Stephen Haven

I am one of those lucky people who have family and friends invested enough in my social well-being to take the time to point out my eccentricities. For instance, I still make my own yogurt, and though in this practice I have always stood alone in my crowd, I nonetheless enlisted those friends who attend yard sales to buy every yogurt maker they found. It took them several years, but I now have four extra ones stockpiled in my basement in the event that the one I have been using finally dies and leaves me bereft. I am prepared for survival.

I also do not care for Wordle, which Wikipedia tells us was played 4.8 billion times over the course of 2023. In this instance I am at the other end of the spectrum, refusing to engage with a phenomenon that is at once wildly popular, and would appear to be a natural draw for a poet such as myself. You like words, so the general argument runs, How can you not like Wordle? which of course is all about guessing the right word within six tries.

I do indeed ‘like’ words, but the stakes have to be right, and not just one word, but combinations of them in artistic array that prompt my curiosity, or stimulate my intelligence, or thrill me with their music, compel me with their imagery, and especially when all of this occurs at once. Stephen Haven’s new collection of poetry is just such an occasion, and we can start with the provocation itself of the title: The Flight from Meaning. There is bravery in preparing the reader to wonder from the outset why the poet would choose to flee from meaning, and simultaneously to raise the question about the directions this flight might take us. I think of one of James Tate’s early books, The Oblivion Ha Ha, in which the title similarly offers an overall philosophical stance regarding absurdity, a conceptual purchase from which to view the potential loss of meaning in the world, though in Haven’s case, humor is not part of the strategy.

For instance, his title poem is a reminiscence in which, during an innocent enough occasion on the beach, he abruptly drops the reader into the heart of his pervading theme. He and his ‘new love’ are strolling in a beach town after a storm, and notice a rainbow that prompts this following set of thoughts:

When the double rainbow shimmered in, we abandoned

The street musician, sat by the ocean-side park

Chewing taffy under those full arcs….

How fully we vanish into them, out of some

Primary edge, the temples of nothing that draw us in,

Light and air, nothing substantially there….

Out over the harbor our still capacity for wonder.

Haven is serious-minded, mature, meditative, and not overly inclined to give in to fantasy. A simple chance to see a rainbow elicits his immediate recognition that the wondrous event is a vacuous illusion: he tells us truthfully that nothing substantially is there. The beauty, the majesty of those towering arcs spanning across the heavens, the colored loveliness—all that draws the poet and his ‘new love’ to sit and admire the spectacle—are nothing more than quotidian sunlight accidentally passing through air containing water vapor. Those are the facts, the truth of the matter, and what he and his new love make of them is mere phenomenological romance—which is indeed the meaning from which people all try to flee: In the flight from meaning, no one fully escapes, the poet tells us, The mass of humanity neither innocent nor guilty…

Neither innocence nor guilt are actual, from Haven’s strict, ontological point of view, but are human constructs and as such are temporal, temporary, and relative to the cultural context in which they appear. Events have significance simply because people say they have it—and, of course, then change their minds, or enter into conflicts with other people who dispute what was said, or how to interpret it. It is not an easy thing to inventory the matters in one’s life that hold most personal value, and conclude both that their significance may fade away over time, and that their personal import is irrelevant from the point of view of Truth.

Nonetheless, Haven is careful to give honest weight to his convictions even when, as in The Absurd Silence of Nature’s Pauses, the circumstances involve the well-being of his son. As the poem begins, the poet offers a collage of images and details that represent what he remembers of his son’s dire illness when they were in Beijing together.

If only you are listening there is somewhere

An old refrigerator straining to beat the heat.

Footsteps from the floor above, the still settling

Of an ancient house. Wind chimes

From your neighbor’s yard, beauty and randomness

Wrapped like serpents around a Hippocratic staff.

He orients himself emotionally by his careful itemization of details in his familiar, domestic environment, which steady him until his anxiety—in the form of those Hippocratic serpents—breaks through the surface to reveal the medical circumstances that are the occasion of the poem itself:

When my son lay in a Beijing hospital

Bit by a bug, listening through 105 degrees…

In the hiss of that hospital room, two continents

Held their breaths, until he was his own

Wind instrument, tones, rests drawn from the air

That filled the gap between his teeth. Without measure

And without end, over slow coffee

The traffic slushes by, a plane passes overhead.

Here we notice the poem concluding with another collage of images, those random events occurring outside the hospital that are no more connected to his son’s fortunate recovery than were the noises of the refrigerator with which his memory began: slow coffee, the measureless streams of cars and trucks slushing by, air traffic far distant above him, and removed from the familial trauma. The poet’s journey from anxiety and fear regarding his son’s survival, to relief and joy, occurs within a larger material context oblivious to the emotional drama.

It is perhaps fair to wonder at this point if value may be found somehow in that human perspective, mutable as it might be. And indeed Haven seems to be pushing us toward that opinion, or at least encouraging us to raise that question. He presents momentous, consequential circumstances that display the extreme contrast between all that is humanly valued (his son’s life, for instance), and all that is inhuman and pointless (the measureless traffic slushing by). With this in mind, let me report that Haven not too long ago gave a poetry reading, during which the poet Deborah Gorlin noted in the conversation afterward that there is another legitimate interpretation of his book’s title: The Flight from Meaning can also be understood as a departure from one meaning to other meanings and valuations—in the way we might leave from Boston and fly to San Francisco. In this sense the flight is an imagined transit from one meaningful point of departure toward another new, creditable destination.

This observation is in fact a key thematic strategy in Haven’s book.

The poet can reorganize the trajectory of his imagination as less an escape from absurdity, and more a track toward humane merit and purpose, and a corollary valuation of the transient and evanescent. He notes that

Out of darkness the ear will lead us. You must be very quiet

To hear blind Milton chanting to his daughter in the space

Our century vacates. So the window of a single rose.

You sit there remembering your father reading

Sunday afternoons, a glass of sherry floating in snow,

Heifetz in Beethoven’s concerto, this wooden wind,

These insects slumbering through

Long gestations of some mind, conjured in quietude.

Equal, Always Equal, to the Inexpressible

Haven in his meditation chooses favored, personal moments in his pantheon of exquisite aesthetic meaning, and adds family connections between John Milton chanting his inspired nightly lines of Paradise Lost to his daughter, who then transcribes them each morning, and Haven’s own family relations with his father. If these are personal values, and are not shared by others who perhaps value Milton less highly—this is possible, after all—, or prefer Tool or Nirvana to Beethoven—well, that freedom to determine individual taste and merit is precisely the point of treasuring the evanescent and inexpressible. The nature of meaning will be individually determined, and broader valuations will need to be discussed in larger public contexts.

But one final, crucial point. One of the implications of a philosophy that treats temporal significations as only apparently real is a resulting lack of ethics among human ideals. Haven is indeed a cultured poet, with a beautiful craft, but he does not limit himself to personal conversations with and about those whom he loves. He is equally adept at entering a public discourse in which he confronts the social turns in this country toward violent intolerance and institutional cruelty. As of the very moment I write this sentence, we are in the throes of a new wave of ethnic persecution as targeted social groups are vilified, gathered up, and deported without due process. Haven has taken notice. In his long poem, Filthy Lucre, for example, he acknowledges both the role of the slave trade in establishing old money among proud white American families, and also his own family’s participation:

We always suspected

My mother’s love of her mythic

Southern gentility. Then in the digital

Head count of an 1830 Census

The “Schedule of Whole Persons

Within the Division allotted to…”

In thin pencil, our ancestors’ names,

Jacob’s Canaan leading the way,

294 slaves.

The historical knowledge in the background renders all the more delicate the complexities of his very personal friendships with Black men among whom he grew up as boys in a blue collar industrial complex in upstate New York, and with friends he made at a local YMCA in Cleveland:

Al called me white boy, meant it kindly,

Asked me over for egg foo young,

A Cavs game on his flat screen TV.

Every house sported the same

One-car garage. Row after row

Tight brick two-stories. He cracked

The front door screen, watching for me.

It’s hard to say these moments, and others like them, are unimportant, not worth recognizing and remembering—even if there is a cold cosmic vacuum hovering in the intellectual background. The two men are loyal to each other over the years, despite both the terrible historical divide, and the different sides of the different cities they live in as adults. They watch out for each other, which I think is Haven’s ultimate point. This is what I walked away with, after reading his book. Ideas are simply insufficient to account for these enduring connections. Haven requires the particularity of relationships to provide perspective, color, and value, by which his poetic vision is completed.

NEW BOOK AND BOOK LAUNCH

My manuscript, Chased by Lunacies and Wonders, has won the 2023 Catamaran Poetry Prize, and is available for purchase at this link: https://catamaranliteraryreader.com/subscribe-donate/chased-by-lunacies-and-wonders

The book is also available on Amazon. And here is the cover:

Trees Grow Lively on Snowy Fields

Here is a link —

https://singaporeunbound.org/blog/2021/12/3/passageways-between-cultures

–to a review I just wrote of a collection of contemporary Chinese poets, Trees Grow Lively on Snowy Fields. The review is published in the online journal Singapore Unbound. Stephen Haven is an American poet who has worked with several native Chinese translators over the course of a thirty-year collaboration, and together they have created lovely translations that offer passageways between distinctly different cultures. I hope you enjoy both the review, and the book.

TELL YOU WHAT

Woodblock Print by Annie Bissett

Woodblock Print by Annie Bissett

Tell you what, the air aloft is falling.

Here it is, October, November, people

on the mountain speak again about

hydraulic jumps and fires. The power is

already down. Personally, I’m on

the wharf in Santa Cruz, but even so

I’m listening for downslope winds beginning

high before descending in a sinking

train of music aiming overland

and tumbling toward me on the coast. I take

a lung-full in, sampling for smoke

arriving from Sonoma. All of us

are breathing it. If I were to die

and then return to earth as horses, running

with the speed of money, I would fly

the flames behind me flaring into canyons,

sweeping through the prehistoric fuels

and towns to overtake the traffic trapped

on chains of roads as conifers exploded

overhead. Are they beautiful,

these evergreens ringed in elemental

force? Wreathed demonically? A problem

I will leave unsolved. If I chose

a bird, I’d be a phoenix to come out

alive and recognized on thermals rising

over vineyards and incendiary

homes. Really, I’d be chasing safety

same as residents evacuating

underneath the haze and rain of ash

to reach as refugees the temporary

camps popping up, and populating

open spaces. Lanterns sparkle here

and there. Someone lucky saved his ass

when chaos drafted every buoyant

movable alive, and separated

friends and families. Circumstances

fly apart so fast. Fathers on

their dying phones are calling children still

on route. Sisters hold out hopes for detours

full of serious grace, which I’m here

to say are unattainable in country

currently alight, and commonly

reset in violent conflagration. Such

derision drives us all to ground.

The Book of Delights

Massachusetts Reviews: The Book of Delights

– BY BRAD CRENSHAW

The Book of Delights: Essays by Ross Gay (Algonquin Books, 2019)

The 2019 Conference of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs concluded this spring, after nearly six hundred panels, readings and celebrations, and over eight hundred vendors and literary presses on display at the book fair—all crammed into three days and three nights. The Massachusetts Review was there, celebrating its 60th anniversary by organizing an excellent, memorable panel, and establishing its presence at the book fair. This conference for writers is, of course, not the only one held this year, but it is the largest, and its organizers were visibly committed to representing as wide a range of topics as writers can imagine—which, insofar as writers are very creative people as a whole, became in practice an admirably diverse program.

Indeed, many agendas were imagined differently than they are currently to be found in our national political climate. The AWP allowed space for writers to set topics for national debate, identify voices that are seldom heard or given credence, promote different points of view, cross gender boundaries, and in general call for resistance to the current political business of factionalism, paranoia, and narrow self-interest.

The virulence of anger and self-promotion at the highest levels of institutional power understandably prompts a rejoining ferocity in the opposing voices. What might be found missing among such voices, however, is an attempt to reach across dividing lines to find some basis for productive collaboration, or to discover a process of healing wounds after exercising cultural wars. Bravery is required to step visibly into the ground separating opposing militants, which is perhaps the first descriptor I want to use as I introduce Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights.

He does not make this claim for himself, bravery, but I think Gay would recognize that it might apply to a writer—perhaps especially a black writer—who, as he does, composes an entire book devoted to daily observations that include the delight he takes in seeing a red flower—an amaranth—growing by chance out of a crack in the street, or a woman stepping in and out of her shoe, “her foot curling up and stretching out and curling up.” He’s very good at finding small, everyday details that prompt intimate satisfactions, but we readers also know that elsewhere white lunatics armed with assault rifles are rushing into black churches to massacre the congregants. One of the risks Gay takes is to be trivialized, accused of ignoring the scale of atrocity as he attends to a flower.

Gay, of course, knows this, and very quickly in response he opens up the definition of delight. Readers might well think, we already know this feeling, but Gay demonstrates that we are incomplete in what we think delight constitutes, and that it is we who are trivialized by our lack of human empathy. This is a severe judgment, but he makes it kindly.

In Gay’s treatment, delight, and its close cousin gratitude, are fundamental experiential capacities: such feelings find and instill value in even unpromising features of an urban environment (flowers by a chain link fence with barbed wire on the top, “just in case”), and they respect the interpersonal gestures connecting people to each other. Most of these gestures are tiny, such as watching that woman with the tired feet surreptitiously take her shoe off. Or the pleasure he experiences when a stewardess on an airplane calls him honey. Or the crazy humor when, during a security check at an airport, the TSA guy asks him where he’s going, and Gay tells him he’s being flown to Syracuse to read poems—and then a few seconds later he overhears the guy “saying to one of his colleagues as I jogged toward my gate, ‘Hey Mike, that guy’s being flown to Syracuse to read palms!’”

Gay will sometimes disguise the nature of his delight by offering it within an apology. For instance, he states “My parents were, mostly, mostly broke people who had neither the time nor the resources to always fix things the boring way, which is called replacement. And so the hatchback, cracked up by a trash truck. . . got fixed with a bungee cord.” His family also used duct tape to secure the hood when the latch broke, and kept a hammer “under the seat to tap the stuck starter until it went completely kaput.” I’ve had to use that trick myself on my forty-year-old diesel wagon, with kayaks strapped to the roof, way the fuck up the Gaspe Peninsula, where a person better know how things work because, let me tell you, you’re on your own. You won’t be calling Amazon for a new starter.

So this last delight is definitely one of my favorites. You just don’t find many people in literary or academic professions who know how to coax life out of an old, failing starter with the judicious use of a hammer. And of course what Gay publishes here is the practical knowledge that poor folks possess, unlike the overeducated crowd who can’t put air in their own tires. He is celebrating the basic competence and ingenuity necessary to keep your life running on track when you don’t have enough money to pay someone else to fix your problems for you. Thoreau and Emerson both would applaud him and his family for a self-reliance that professional economies condemn nowadays—because, by definition, impoverished people don’t spend a lot of money. He is reversing the common valuation.

And because he is a poet, Gay can also value the nuances possible in certain turns of phrase, such as “I need X like I need a hole in the head”—which, as he indicates “means I do not need X. I need to be fired like I need a hole in my head. I need this cancer to resurface like I need a hole in my head.” The occasion for mentioning this particular expression is the documentary on Vertus Hardiman, a black man who, as a five-year-old child, was made a subject by white scientists in a human radiation experiment, in which he was exposed to high levels of radiation that, in his instance, burned “a fist-sized hole in his skull, flesh and fat glistening.” Gay concludes this particular entry by noting “I’m trying to remember the last day I haven’t been reminded of the inconceivable violence black people have endured in this country. When talking to my friend Kia about struggling with paranoia, she said ‘You’d have to be crazy not to be paranoid as a black person in this country.’”

And yet he isn’t—neither paranoid nor crazy. He is writing a large book on delight, which includes, though is not limited to, the delight to be had in social resistance—such as his insistence on calling out white scientists who experiment on black children. Such as the delight his brother enjoys in owning a house in Pennsylvania, which “had a clause in the title that prohibited it from being sold to a colored person, which he is (indulge the anachronism; it was in the title).” This is the same brave delight he takes in appreciating their parents, noting that “As my mother gets older, and in moments of openness, she has begun sharing more of her early life with my father—the family stuff, the this-apartment-is-no-longer-available stuff, the you-have-doomed-your-children-they will-be-fucked-in-the-head stuff. . . She told me my dad, to whom she was married for about thirty-five years until he died, said to her early on, ‘I might be making too much trouble in your life. Maybe we shouldn’t do this.’ But, you know, they did.”

In this one anecdote, as in many other of his daily entries scattered throughout his generous book, he wants explicitly to acknowledge the tensions inherent in what he means to convey by his term, delight, which in his mind is kin to what Zadie Smith concludes regarding the nature of joy. Gay notes that she “writes about being on her way to visit Auschwitz while her husband was holding her feet.“ “We were heading toward that which makes life intolerable” Smith writes, “feeling the only thing that makes it worthwhile. That was joy.’” She continues in this line of reasoning to conclude that “the intolerable makes life worthwhile”—which is a position Gay himself comes to agree with, though he infuses the idea with his particular belief in community: “What if we joined our sorrow,” he writes. “I’m saying, What if that is joy?”

This is a humane vision, a vision of social affinity, for which he assembles a chorus of supporting voices that include not only Zadie Smith, but the Japanese novelist Kenzaburo Oe, the poets Phil Levine and Rainer Rilke, the filmmaker Paolo Sorrentino, and Bethany, who was one of his students. Gay has a democratic and generous spirit. He wants to promote, in his own words, “the simple act of faith in the common decency, which is often rewarded but is called faith because not always.” He can, in fact, find instances of failure in common decency within his own behaviors. He is not a naive man, but a person who hopes to overlook or overcome momentary failures in people while expecting better of them. “I believe adamantly in the common decency, which grows, it turns out, with belief.”

Before turning you loose to read his book, I’d like to call attention to one more delight. Gay points out that at times his belief in common decency struggles against the cultural intent—by which he means chiefly white culture—to commodify suffering, especially the suffering of black families, by turning it into television entertainment. The particular source of his observation starts with a podcast about Whitney Houston’s early career, “which some channel,” he explains, “decided ought to be a reality television show, and which, from the sounds of it, a lot of people thought made good TV.”

And he goes on to imagine how that show might have gotten started, the pitch needed to convince producers to fund such a program: “I imagine you have to have meetings and secure producers or directors, get a budget, things like that. Many decisions and agreements have to occur, probably many handshakes, some drinks, plenty of golf, trying to figure out how best to exploit, to make a mockery of, a black family, the adults in which have made some of the best pop music of the last thirty years.” “I have no illusions,” he adds, “by which I mean to tell you it is a fact, that one of the objectives of popular culture, popular media, is to make blackness appear to be inextricable from suffering, and suffering from blackness.”

The proof that this equation is false is the book itself: “You have been reading a book of delights written by a black person,” he points out, “A book of black delight. Daily as air.” In The Book of Delights, Gay has published a vision that he is trying to make available to everyone—all races and ethnicities—though he is not insensitive to the odds. Delights may be daily, but they do not come cheap; they need earnest effort and sustained belief. They also require a soul like Ross Gay, who is sensitive to possibilities, ready to be pleased with people for better or worse, and who is willing simply to share what he has seen over the course of his forty-fourth year of life, from one birthday to the next.

Virginia Woolf at Night

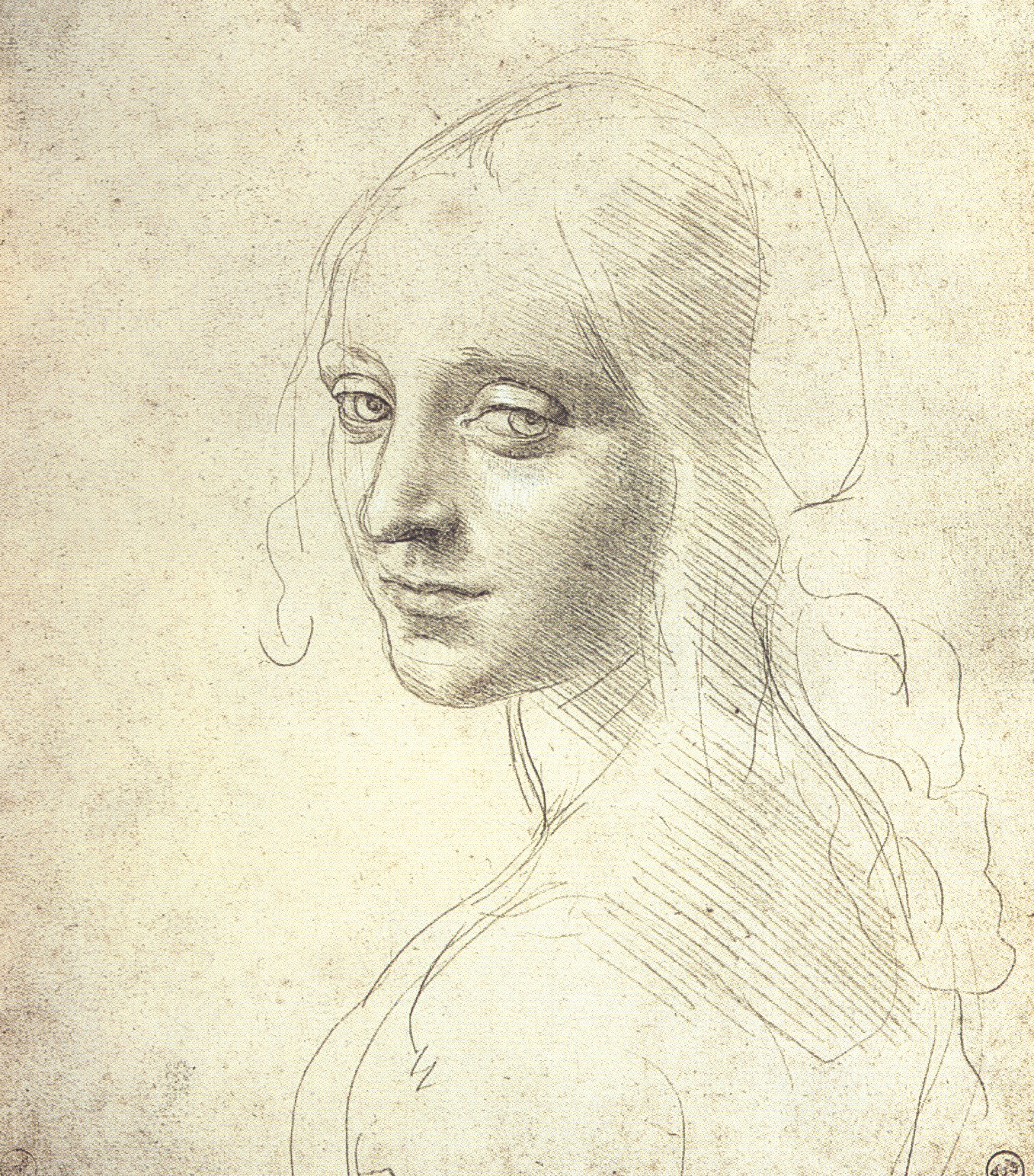

Well, no, the image above is not a portrait of Virginia Woolf. I suppose, properly speaking, it is not even a portrait per se, but is simply one of Leonardo’s many studies drawn in silverpoint as he collected figures he thought he might use one day in a painting—or perhaps to capture an expression, a cast of mouth, a glance that he saved for later use in his art. His days were long before there were any means of preserving what was seen—except by marks made by hand. This drawing is obviously unfinished, both insofar as her hair, shoulders and back are mere sketches, and also as her left eye is somewhat too large relative to her right eye. From our contemporary point of view, the drawing is masterful, immediate and expressive—and worth a fortune. But there is no indication that Leonardo considered it up to his standard for the serious business of his art. It is just a study, like the many others he has crammed together on scraps of paper, and in his notebooks, of old men, hags, grotesques, young men and women, anatomy lessons, and far-fetched inventions.

Virginia Woolf, for her part, and in service of a different art form, worked on her human studies in her Diary. She favored writing while seated in an easy chair with a writing board in her lap. She used an ink bottle and a steel-tipped dipping pen, and wrote by hand at considerable speed without making corrections, editorial revisions, or authorial re-considerations. It is in this sense of immediate impression that I mean to emphasize when I call her Diary a daily series of studies: she is sketching her conjectures of people, in a prose style instant and unpondered, using diction that occurs to her on the spot, at that moment, to express ideas she is capturing just as fast as she can write them down.

Those contemporary readers new to her Diary might be most interested, at least at first, in her observations of famous people. For example, the first time she met T.S. Eliot occurred on November 15, 1918, and she writes: Mr. Eliot is well expressed by his name—a polished, cultivated, elaborate young American, talking so slow, that each word seems to have special finish allotted to it. Beneath the surface, it is fairly evident that he is very intellectual, intolerant, with strong view of his own, & a poetic creed. Here is a penetrating estimation of Eliot’s character, formulated over a half-hour social exchange, which remains prescient even after a further century of research into the poet’s letters, prose writings, poetry and biographical study. As she indicates, she sees through surfaces, however refined, and incisively sums up what she finds hidden down there.

She is delighted by social absurdities, such as an exchanged conversation told to her when King George V, during a Royal visit, at one point turned & asked Princess Victoria where she gets her false teeth. “Mine”, George exclaimed, “are always dropping into my plate: they’ll be down my throat next” Victoria then gave a tug to her front teeth, & told him they were as sound as could be—perfectly white and useful. Even in an era of personal disclosures among American political figures, whom you’d think would know better, comparisons of false teeth are pretty funny. In this vein she also reports discussions regarding self-abuse, incest and the deformity of Dean Swift’s penis.

More commonly she relates the quotidian ebb and flow of English life around her. And though she is not a naturalist, she does write frequently in the early years of her Diary about the full moon—though probably not for reasons you might imagine. She begins her journal in January, 1915, stops it six weeks later on February 15th, (for reasons I’ll get to later) and then resumes it again in earnest in October 1917. During these years, the First World War was raging, and German airships—chiefly zeppelins at that time of the war—floated across the English Channel to bomb London when the city might be illuminated by moonlight. Without the moon, nighttime visibility was impossible, insofar as the lights in the city were otherwise blacked out. In a characteristic entry, Virginia wrote on October 22, 1915 that “The moon grows full, & the evening trains are packed with people leaving London. We saw the hole [caused by a bomb detonation] in Piccadilly this afternoon. Traffic has been stopped, & the public slowly tramps past the place, which workmen are mending, though they look small in comparison…Windows are broken according to no rule; some intact, some this side, some that.

On December 6th, the moon rose later, after 11:00pm, so the zeppelins did not arrive until 5 in the morning: I was awakened by L[eonard] to a most instant sense of guns: as if one’s faculties jumped up fulling dressed. We took clothes, quilts, a watch & a torch, the guns sounding nearer as we went downstairs to sit with the servants…wrapped in quilts in the kitchen passage…Slowly the guns got more distant, & finally ceased; we unwrapped ourselves & went back to bed. In ten minutes, there could be no question of staying there…Up we jumped, more hastily this time….In fact one talks through the noise, rather bored by having to talk at 5 a.m. than anything else. Guns at one point so loud that the whistle of the shell going up followed the explosion. Cocoa was brewed for us, & off we went again. Having trained one’s ears to listen, one can’t get them not to for a time; & as it was after 6, carts were rolling out of stables, motor cars throbbing, & then prolonged ghostly whistlings, which meant, I suppose, Belgian work people recalled to the munitions factory. I have never been bombed, never had to flee the prospect of floating airships intentionally dropping high explosives on me to wipe me out, and devastate my habitable city. But if I ever am to be bombed, I hope I have enough courage and civilizing imagination to allow hot cocoa, shared among companions, to assuage my anxieties.

As I suggested earlier, most of her entries center on human observations in situations when she is not actively under fire. Here is one of many attempts to register the points of character of Lytton Strachey—a friend, and the author of Eminent Victorians: He is one of the most supple of our friends; I don’t mean passionate or masterful or original, but the person whose mind seems softest to impressions, least starched by any formality or impediment. There is his great gift of expression, of course, never (to me) at its best in writing; but making him in some aspects the most sympathetic & understanding friend to talk to. Moreover, he has become, or now shows it more fully, curiously gentle, sweet tempered, considerate; & if one adds his peculiar flavor of mind, his wit & infinite intelligence—not brain but intelligence—he is a figure not to be replaced by any other combination. She is writing about mere friendship here, which she considers at length, with sustained perception. She is not casual about her friends, but derives a nourishing pleasure from them, and with them, which does not diminish over time, but is consequential, and abiding in substance. She can be vigorous, humorous, entertaining, frank, unsparingly critical—but never trivial.

With that said, she was not merely concerned to write about friends in her Diary, and about people in high society, but she was interested in everyone. In Spring of 1917 she and Leonard were able to buy their printing press, which they set up at Hogarth House (Hence Hogarth Press), and thereafter spent some time trying to hire people to help them set type. Every single letter, punctuation mark, and space between words had to be set by hand, which required sustained attention to detail, and a certain strength of mind against tedium—which was not possessed by everyone who applied for the job. Barbara was one such person: Happily no apprentice today, which gives us a sense of holiday. We have had to make it rather clear to Barbara that this job may not be followed by another. She refuses payment for last week. So there’s no fault to find with her. No one could be nicer; & yet she has the soul of the lake, not the sea. Or is one too romantic & exacting in what one expects? Anyhow, nothing is more fascinating than a live person; always changing, resisting, & yielding against one’s forecast; this is true even of Barbara, not the most gifted of her kind. Virginia is never one to pull punches, which makes her obvious empathy and delight all the more authentic. Nothing is more interesting than a live person.

It is worth noting that she did not extend that interest toward introspection. She writes about others, not herself. That stoppage I mentioned in her Diary starting in mid-February, 1915, was prompted by her descent into a particularly virulent lunacy. On Monday, February 15th, she writes with her usual perspicacity about the people she encounters in the London shops, meeting Walter Lamb by chance, and rambling down to Charing Cross in the dark, making up phrases & incidents to write about. Which is, I expect, the way one gets killed. The very next day on the 16th she had a headache, which heralded her slippage into madness. By the first week in March she required professional care, and for months thereafter she was incoherent, violent against herself and others, and so densely insane that professionals and family alike doubted she could ever return to anything resembling a normative state of mind.

She did return, of course, and resumed writing her Diary in early August 1917. However, she never provided a single solitary word about the reason she lapsed in her daily discipline of keeping her Diary. She never mentions that she had a break in her sanity, never made an observation about the nature of her mental state, no word to characterize the quality of her consciousness, no statement of what it felt like, no memories of delusions, no lamentation about lost life during those awful months, no promises, no allusions, no apologies to others for her behaviors, no regrets for the harm she inflicted on other people. No mention whatsoever. One day in 1915 she writes about touring London shops for books, and the next entry on October 8, 1917 in her Hogarth House Diary she begins with another accidental encounter with Walter Lamb in London. A seamless continuity belying the two-and-a-half years silence.

Her creative imagination, even in her personal Diary, operates on principles quite other than contemporary intentions and aesthetics. At the bookstores we now have our choice among works focusing at length on lawn sprinklers in the author’s childhood, professors analyzing their lives among students and fellow teachers. IRL Streamers entertain their audience in realtime with attempts to pick up young women encountered on the street. Being offensive is the point of the entertainment. Virginia Woolf in her private, unpublished moments thinks about people who are other than herself. Apart from the healthy display of empathy, what a basis this is for a political stance.

It Occurs To Me That

Years ago you might have thought, as I

did once, faring among the farthest crowds

of islands, unbearably green, in Polynesia,

ringed with stone gods,

that I had dodged

ancestral prophesies, and finally

was shut of ghosts, momentous gossip and

the family doom. I mean, I absolutely

thought I cleared my mind. For years I slept

beside the blue-eyed ocean, courting every

hour pouring over in the surf

among the agile muses on their boards

by day, and on the beach by night, by fires

beneath a wash of stars handsome in

the high air.

So yeah, once you might

imagine I had lunged safely off

from my accomplishments and ends. My latest

lovely failure at the time had thrown

me out, amicably,

and I eloped

exactly over burned bridges to

escape the facts and sad truths passing

for a way of life I thought was mine.

I’m grateful for my enemies. I made

my way to California, with its brimming

coasts, its pools of disenchantment and

regret,

and those extravagant beliefs

in earthly reinvention, promises

of safe sex, not to mention transmigrating

joys, as witnessed on the glistening beaches

blanketed by actresses and beauties

browning in the sun of their ambition.

Pelicans offshore would swoop for food

on bent, pirate wings, while in the baseless

air, gulls dropped like raucous angels

tossed from grace. It takes me back, as if

I never lived in sight of tricks, or missing

persons rolled inside of plastic sacks.

I was roused, and rough in my instruction,

dazzled in the blue winds always

in the way, rendering the far-

away schooners blue at sea. They moved

me like an errand in an unknown land,

like promises, like rules I’d better try.

So far, so good. Near at hand, drag

queens were holding court in force against

the less-gorgeous mortals put on earth

obscurely, whose broken spirits dried their bones.

White men slept on graphic towels, and burned.

Meanwhile, movie extras practiced unexpected

love, and off around those fucking palm

trees, quarterbacks kept making plays

all day, and scored. Everyone auditioned as

adults. On mats, amid the pandemonium,

were golden body builders lifting their

eternal weights, and taking steroids sold

by lab assistants winging frisbees onto

precessed lyric vectors.

And well, yes,

since you asked, I was carried off

by whole cloth, and left not a rack

behind of Baptist trash, but worked on boats

holding melons, and manned the harbor tender

when I could, escorting visitors

to shore for tips. One time, late,

with weather coming in, I ferried to

a ship the size of dreams a shimmery, drunken

star bestrewn with jewels and ropes of pearls,

but minus shoes

—of whom was born, of course,

a famous trail of love, not unusual,

and who would later drown unfairly, I

should add, in another season, near

a Channel Island—

years, however, after

I politely heaved her lithesome body

into bed inside her reeling cabin,

feeling generous and grandiose,

as if I had new teeth. Whereupon

I lurched precipitously, pitched backwards,

and was thrown away entirely as

the schooner slued round, hugely, as

I heard it, in the mounting wind. I hurtled

like a lost comet, crashing on

a davit, while a deckhand madly slipped

the anchor, and we plunged away like horses

into foam and swell, with me in tow.

What may not be wonderful about

abstraction? what is this world? to be plucked

from one dimension, and deposited

with bruises innocently in some midget

cosmos run by half-deities,

half of whom were sickened by the yaw

and ocean roll engendered by Pacific

squalls—which usually are marvelous

when seen from land,

but in their ardent midst,

I’m here to say, the morning blew its smokes

on board, and thunder followed close on thought-

executing fire, the sum of which

de-magnetized the common sense of Hollywood.

Someone brought an ocelot they called

Naomi, who escaped her cage, and once

the winds decayed a bit, the weather settled,

she would climb the masts, and slink along

the yard arms stalking sea birds as they roosted.

Lavishly, she pissed backwards in

the rigging, which appalled the yardmen when

they reefed sails that simply reeked of pheromones

designed to carry miles inside a jungle,

and arouse erotic promise, for

a price. A tactic old as war, if truth

be told about it. If truth pertains at all.

Honestly, you wouldn’t either want

to risk inflaming the illiterate ocean

gods, a volatile lot by history,

nor rub the nether spirits up to rock

your bones with animal abandon, in

your wooden shelter, bobbing on the insubstantial

elements.

And since, to some minds,

by closely defined reasoning, I was

a stowaway, and hoping to have all

charges dropped, I peaceably agreed

to clamber to the topsails, trailing strings

of bloody sausages, and lumps of steak,

with which to tempt Naomi to her cage.

On balance, little could be easier.

Conceding how I cut my teeth on the family

wolves, and those invisible snakes coiling

through my nightmares—well, I wasn’t

discommoded by an ocelot.

Aloft together, we were clearly without

secrets when Naomi leapt symmetrically

to the crosstrees, with her jungle eyes

lighting up the red meat I

extended. I made her reach across me, and

adeptly show her teeth to draw the ligament

of raw beef away. And so it was

I fed her appetites. She slipped into

my lap, her demon body purring like

a tractor, and licked the wisps of blood between

my fingers. I took her collar off, which let

her swallow,

and from the main top watched the chief

navigational stars we followed spark

around me in the changeling darkness, vast

and starlit. Once I started getting cold,

I led Naomi down below for water—

where I peed into her litter box

to dominate her thoughts, should cats have thoughts,

such as they are. At heart, we both were built

from parts of blocks of sapience and feeling,

so it was alright. Naomi played like Rilke’s

phantom in her cell, where I fed

her by hand, by the way, daily—

and to

the point, we neither one were disinvited

from the schooner once we sighted islands

off the blessed coast of Mexico:

Islas Marietas, each about

the size of any whale that breached around

us. Pods of dolphin following, we ghosted

to the gateway port. A motor launch

collected our celebrities, and sped

away to parties, and exotic matters

prearranged by fame—which left the rest

of us to shave, and draw our wages. The bosun

promised he was going straight, and disappeared.

I was given to the cook, who took

me off to market to replenish stores

of ostrich meat, more beef, vanilla

pods and chocolate, tons of onions,

abalone in the shell—and who

relentlessly was preaching. There were rules

against stealing chickens, I remember.

He was strung out on a man, and left me with

the avocados, and my awful Spanish,

while he looked him up, returning with

a brilliant dancer, whom he introduced

with loud, resounding empathy, as usual

with him. They wandered way beyond their destiny,

while I foresaw our market purchases

on board, and stowed within our many-benched

vessel–

though it was another year,

another boat, and in another port

before I understood the rules regarding

chickens. By then I’d beached in Polynesia:

let’s see, Cook Islands after pearls,

and Samoa twice, where I sacrificed

at shrines to the sea-goblins. I weathered

older furies in New Zealand in

the winter rains, representing to

my mind a truly vengeful beauty. White

sharks struck at table scraps and butcher’s

offal I tossed over for the spectacle.

Big-winged birds suspended in

the wind in my line of sight for miles.

Otherwise the latitudes were lonely–

bright, for sure, as every source of light

would scatter oceanic glitter, but we were on

our own. Below us rolled a rogue wave

now and then, exposing unexpected,

wrecks, and drowned roots of islands. From

her golden throne, the moon-faced goddess watched

for small mistakes.

Those who know about

my seamanship have said I’m upward man,

and downward fish, but I was unresigned.

Most cooks aren’t lost at sea, maybe

one in ten some years, out in haunted

waters. Nonetheless, in Mexico

again, on land, knowing what I know,

I wandered inland after ocelots,

and soon was hunting caves, with bats like tiny

demons squealing from the core of solids

all about illegible truths and prophecies,

reminding me of home.

An Unseasonable Soul Holds Forth: The Poetry of Robert Pinsky

Have you ever encountered a movie star or television personality in the real world—in the flesh? Such encounters used to be relatively common in Southern California, in the 60’s and early 70’s—and maybe they still are, given the pictures posted in People magazine or Star, in which you can study various famous people caught shopping without their make-up on, or wearing their bikini’s and gym shorts at the beach. In my experience, on occasion during the summer, you might encounter sundry movie personalities, such as Arnold Schwarzenegger lifting weights on Muscle Beach, or John Wayne among the yachts in Newport Harbor (I once tossed him up a beer to the deck of his giant schooner from my tiny sunfish—which he caught one-handed. He was pretty good.).

A more reliable strategy had people attending Hollywood funerals of someone in the Industry—to which other stars might flock to pay respects, and to display loyalty to the studio at which they hoped to make their next movie. The common, non-famous people were kept a discreet distance away by police tape, but we’d all be out there taking notes in little black books the way serious bird watchers tally the different species they have seen. Instead of Water Birds, or Raptors, we might have Action Heroes, Villains, Romantic Leads, Female Cops—or a newly recognized species, Sexual Predators.

I was dragged along to a couple of these funerals by the mother of a friend of my-then-girlfriend, where I was surprised to discover that none of the movie stars looked like themselves. I never would have recognized Angie Dickinson, for instance, if Robbie’s mother hadn’t loudly pointed her out. For one thing, she was emaciated, which on television looks more appealing than in life at a funeral. Jimmy Stewart I might have guessed, but only because of the context: I was expecting to see someone famous, and here was a tall, nondescript, skinny guy in a suit. He resembled my grandfather on a Sunday. The moral was, everybody looks better on the screen—except maybe John Wayne, who seems never to have gone out of character.

With this precept in mind, then, let’s skip ahead to a reading I attended not long ago that Robert Pinsky gave at the Smith College Poetry Center, which was an opportunity to be reminded just how good a poet he is. Having seen him on The Daley Show kibitzing with Jon—on which he looked glamorous, suave, and in good humor—I was curious to greet him again in person in the familiar surround of poetry readings everywhere: those underground, windowless rooms that most colleges and universities seem to reserve for poetry readings. Here there is something in the aesthetic of a bomb shelter: at least we’ll all be safe in bad weather. Pinsky of course has done this before, and looked as comfortable and personable as he did on television, and as engaged as ever in the communal sharing of poems and poetry—his, in this case.

But he has always been committed to the public good. His tenure as Poet Laureate was remarkable for the outward-looking aesthetic he espoused. As Laureate, he was clearly in public office, and created the Favorite Poem Project that continues to engage social media, and to democratize poetry. In one fell swoop he ushered poetry out of the closed academic towers, and opened it to the untrained, non-specialized, generously peopled world at large. The age range of participants is also non-academic, extending from 5-year-olds who had favorite poems, to a 97 year-old gentleman. The shared characteristics of those who are now archived in the Favorite Poem Project represent a far greater demographic of Americans than any other program in any other English Department anywhere.

We see a similar omnivorous instinct in Pinsky’s poetry, both in his diction, and in his subject matters, which have consistently looked with interest and perception into the chaos of social orders. And whereas in his latest books he has famous, individual poems that confront events of note in the civilian world outside the academy, earlier in his career he devoted entire books to civics. He is a man of the world, as his comfort on television demonstrated, and engaged in holding up its features for public scrutiny. His autobiographical sense of himself, in other words, is cosmopolitan. He imagines a world that is apart from himself—in fact, a world in which he does not personally participate, but a world nonetheless that he imbues with his emotional investment, so that the subject involves his emotional life, his personal choices, his psychic activity.

His particular, literal use of autobiographical material is striking. He commonly avoids the extremities of confession, and the exclusions of redemption. His discipline is an historical accuracy that sets the poet, intact with his particulars, amid the larger contexts of familial, social, political and philosophical cultures. He is neither the elegiac alien of history we find in a poet such as Berryman, nor the historical despondent we have in Lowell, but is an historian per se: one who chronicles the world’s events and–“Compulsive explainer that I am” (An Explanation of America)–explicates the truths they will tell. His history is inevitably personal since he is humanly individual, and so bound by the conditions of time and place, by identity, temperament, knowledge and experience. But his poetic enterprise is not meant to celebrate the personal emphasis of events–private and public–that affect him. As his second book makes explicit, An Explanation of America, he likewise cares to interpret for himself and others the larger systems of intelligibility, the superstructures encompassing and, to a large extent, directing the local circumstances of character and station. His purpose, then, is a dual one, in which he brings into relief the characteristics that distinguish us as the people we are, living when and where we do, in America in the modern era; and discriminates between our collective traits and those we hold separately.

“A country is the things it wants to see,” he writes, and then proceeds deductively to disclose the logical correctives to individual autonomy exerted by his historical condition: “If so, some part of me, though I do not,/Must want to see these things….” The declaration reveals the constitutive force of the aggregated nation, whose economic manipulations and mass psychologies transcend the poet. He is constrained in “some part” of himself–to which he professes little conscious access–to want among other things “to see the calf with two heads suckle;/ …to see the image of a woman/…Swallow the image of her partner’s penis.”

Our individual pursuits are likely to chafe under the oppressions of national will, the pressure of whose universals squeezes particular aspirations into sympathetic conformity. Pinsky can dissent (“though I do not”) from that conditioning, from that part of himself for which he is not the origin, which indicates his dissent from the norm, his polarization that sets against the national average both the essential privacy of the self, and its gestures toward autonomy. The intimate center resists the assaults of the historical process: “Against weather, and the random/Harpies–mood, circumstance, the laws/Of biography, chance, physics–/The unseasonable soul holds forth,/ Eager for form…” (“Ceremony For Any Beginning,” Sadness and Happiness).

The self holds forth against the sciences of its physical conditions, the ungovernable conundrum of its circumstances, the influences of its neighborhood, the flux of its own emotional nature–out of all of which the self induces the different generalities of its identity: it is “Eager for form.” Such eager resistance is not merely a selfish descent from responsibility, but rather is a logical corrective to the deductive abuses of social custom. For if it is true that the individual is part of the country, and so is conditioned by what the country wants to see, it is no less true that the individual as a citizen constitutes, however partially, the whole of which it is a member. Responsibility, in fact, would seem to be a reciprocal relation between public and private voices, with the latter declaring its opinions, explaining its personal longings and thereby serving as a caution to the tyrannizing systems of national values that are erupting so visibly as I write this—as President Trump and his Republican accomplices use social media to manipulate and indoctrinate a gullible, unreflective public.

The conflict here is a venerable one between the collective, with its determinist orders and prohibitions, and the individual, with his felt autonomy and experiential freedoms. The important thing to note in Pinsky’s poetry is his typical refusal to capitulate to either extreme. He does not unduly value the formalisms of national will, nor does he unduly celebrate his release from those normalizing orders into, as he might imagine it, the original space of selfhood. He centers himself instead between the poles, and–this is the point–treats each as an intellectible complex embedded within the larger protean medium of language. There is no one origin of meaning, no central, presumptive authority: no matter how intimate or how public the issue, neither individual opinion nor institutional definition inaugurates its desire in a vacuum, but indeed each introduces its respective values into the commerce of mutual interpretation, compromise and difference.

Such an entangling variance of interpretation is a boon to individual freedoms since it multiplies possibilities not ordinarily available in the binary system of citizen and country–or, in the terms of our Cartesian logic, self and other, particular and universal. Language is the great solvent in which all participants dissolve, and out of which our temporal vocabularies precipitate. But this semantical chemistry complicates the individual colonization of our times and places since its complexities often give up in decisiveness and clarity what they win in flexibility and particularity. Pinsky is enough indebted to the modernists, at least in his first book, to construe the natural or “real” world as a difficult chaos, blank of significance, that resists our attempts to settle it. He grants it a promise, “but a promise/Limited, that sends folk huddling to their bodies/Or kitchens as colonizers of the day/And of the year, rough settlers who throughout/The stunning winter couple in a fury/To fill the brown width of their tillable plains (“The Time of Year, The Time of Day,” Sadness and Happiness).

This fury to domesticate the wide and empty plains is at once hurried and desperate. It prompts not only the sexual urge to populate, to fill with an urban sprawl the desolate spaces of the prairies, but also the concomitant urge to relieve the wintry absences of meaning with human speech. We should note the implied equation between the need for human presence, probably sexual, and for language: “One way I need you,” he begins his poem, “the way I come to need/Our custom of speech, or need this other custom/Of speech in lines, is to alleviate/The weather, the time of year, the time of day.”

But the alleviation is, and can only be temporary, given the situated character of speech and identity. The temptation , then, in which Pinsky indulges on one notable occasion, is to construe the historical flux as an absolute defeat to understanding, and to counsel the relativity of meaning. Such is the advice of the title poem, “Sadness and Happiness,” in which the poet examines the nature of those generic humors. He explains: “That they have no earthly measure/is well known…Crude, empty/though the terms are, they do/organize life….” The discrepancy between the crudity of our emotional counters, and their organizational importance in our lives is troubling, for it means not only that our sentiments, but our dispositions and perhaps the ethical means of our actions (“the pursuit of happiness”) are formulated by a semantics that, he claims here, has little or no bearing on our earthly realities. Where else they might have their appropriate measure, if not amid our sustaining contingencies, is moot since sadness and happiness are “deep/blank passions, waiting like houses” to be inscribed by our idiosyncrasies, and like houses ready to enclose us in empty domestications, in the crude fictions of neighborhood mores. The terms inspire a “bullshit eloquence,” bullshit because measuring little in the world beyond our private likes and dislikes–though even then they are liable to confuse what we think we know about ourselves: “the surprise is/how often it becomes impossible/to tell one from the other in memory.”

If our semantical environments within which we hedge our experience, cultivate our aspirations and enthrone our ethics have, as the poet claims, incomplete or inappropriate relations to our daily incidents and conditions, then we are sure to be chastised by the social and natural worlds excluded by our eloquence. Our conversations will be to little point, our desires incapable of bringing anything to birth amid nurturing fact. We will have, in short, a discourse leeched of its practical applications, though potentially rich in the intransitive sensitivities of fine taste and delicate feeling. The consequences of such locutions are not desirable, which, if not exactly the point in “Sadness and Happiness,” is very much an issue in other of Pinsky’s poems, particularly “Essay on Psychiatrists” and An Explanation of America. He is concerned to show us how our ideals–what we think we want–abuse us. For those who are content to abandon the outer world, however, preferring the resonances of their aesthetic languages as they sound an authentic desire, an exact longing, the poet does admit that “somewhere in the mind’s mess/feelings are genuine, someone’s/mad voice undistracted, clarity/maybe of motive and precise need/like an enameled sky” (“Sadness and Happiness”).

But as he is careful to distinguish, this is a “mad voice,” one unrevised by reason, which is unavailable, and uncounseled by prudence, which is indeterminable. The so-called clarity is that of obsession, of a denuding and destructive passion: “the heart is a titular,/Insane king who stares emptily at his counselors/For weeks, drools or babbles a little…and points/Without a word…Toward war, new forms of worship or migration” (“History of My Heart.”). that this kingly heart is innocent of real consequences, because innocent of reality, does not redeem either its insanity or its viciousness toward those people reified as objects of its desire.

Nor will an appropriate self-consciousness necessarily save the aesthete from his debilities. The answer to mad innocence is not merely a flight to its opposite sophistication, whose enlightenment, because thoroughly versed in the history of ideas, is skeptical of them all. This is a Stevensian aestheticism, a belief that we are rescued by our lack of authority, by foreknowing the pretense of our best efforts at locating truth, and therefore refusing to be deluded by either their partial successes or their inevitable revisions. Such also is Pinsky’s conclusion in “Sadness and Happiness,” though he is not content with it. For he well knows that the final advice given by our supreme fictionalists is paralysis and despair.

If no human statement is legitimate, then no premise is capable of sustaining action–the lack of which is a luxury neither the poet nor anyone he loves can afford. “It is intolerable/to think of my daughters, too, dust–/el polvo–or you whose invented game,/Sadness and Happiness, soothes them/to sleep,” he writes, and thereby uncovers the menace to those lives organized by the “invented game,/Sadness and Happiness”–the menace that he has had on his mind all along. His “Bizarre art of words” has aimed to transmute death’s objective threat to well-being, but since no moral imperative can be discerned among the aesthetic enclosures we tell ourselves–any one of which is as valid and as invalid as any other–he has won only a heightened sensitivity to his many failed poses, his temporized, staged manipulations. He is “Always distracted by some secret/movie camera or absurd audience” from the true ethical end of his actions, from some authentic teleology whose virtue would be the escape it provided from the existential modes of life: “art and life/ Each both inconstant mothers,” he concludes, “in whose/fixed cold bosoms we lie fixed,/ desperate to devise anything, any/sadness or happiness, only/to escape the clasped coffinworm/truth of eternal art or marmoreal/ infinite nature.”

If we do indeed lie fixed amid our artifices and marmoreal nature, then how much more reasonable might it be to consent to their limits, than to treat them as if they were not the necessary conditions–the fixities–we conclude they are. Because it is hostile to the givens of biological life, this defiance of imperatives is a love of death, whose irrationalities the poet examines in a thematic subsection, “A Love of Death,” in An Explanation of America. The attempt to transcend the historical process is not a strategy Pinsky has entertained personally, as we might assume of the aestheticism in “Sadness and Happiness,” but it is nevertheless a characteristic prominent in his idea of America and Americans. It is also a pretense, as he understands it, a mistreatment of idealism that, in order to disguise its real cost, disarms one’s mental acuity by appeals to infantilism and to adolescent sexuality. Consequently, in order to show both its romantic seductiveness and its real ethical bearing, he imagines the same deadly transcendence twice, first to offer it at its most inviting, and then to expose its delusions.

In an image recalling the empty, “enameled sky” of insane clarity, he begins his picturesque transcendence by introducing a child into the American prairie and its “pure potential of the clear blank spaces”: “Imagine a child from Virginia or New Hampshire/Alone on the prairie eighty years ago/Or more, one afternoon–the shaggy pelt/Of grasses, for the first time in that child’s life,/Flowing for miles.” That it is a child-protagonist is Wordsworthian in its significance, for the vision evolves into a gentle union between the sentient human, and a beneficent nature that is inviting in its strangeness: “Ground-cherry bushes grow along the furrows,/The fruit red under its papery, moth-shaped sheath./Grasshoppers tumble among the vines, as large/As dragons in the crumbs of pale dry earth.”

This is a world of romance, its grasshoppers appearing to the child, “Head resting against a pumpkin, in the evening sun,” as fantastic, harmless dragons amid the Edenic bounty of a garden, whose virtues are those of innocence, a peace of mind and spirit, a harmony among the constituents that releases the child from the stridor of differences. “The bubble of the child’s heart melts a little,” we are told, “Because the quiet of that air and earth/Is like the shadow of a peaceful death…Where one dissolves to become a part of something/Entire.” That last dependent clause is the operant line, the statement of desire that manipulates the visionary attitudes, arranges the significations, and settles the outcome of the transcendence. The child is transfigured, ushered into a presence so universal that “whether of sun and air, or goodness/And knowledge, it does not matter to the child,” who is “happy to be a thing” among all other things in the creation.

The visionary longing likewise fudges its realities, since if the child is indeed rendered into a “thing,” then it can be neither happy nor unhappy. The penalty for its particulate dissolution into the universal bath of “goodness/And knowledge”–which are undefended givens inhering in “sun and air”–is the loss of its sentience, its intelligence, without which the question not only of happiness or unhappiness, but also of goodness and knowledge is irrelevant. In other words, the child’s successful transcendence, which is death, treats as spurious the very premises–innocence, goodness, knowledge, peace–upon which its presumed agreeableness is grounded.

Pinsky handily exposes this fallacy, and undermines as well the romance of the child in the garden, by adjusting the principles of the vision according to actual or probable circumstances. So in the midst of that same prelapsarian prairie we are asked to imagine “Some people are threshing in the terrible heat/With horses and machines, cutting bands /And shoveling amid the clatter of the threshers,/The chaff in prickly clouds and the naked sun/Burning as if it could set the chaff on fire.” The natural comfort assumed in the child’s version becomes the more likely stifling, oppressive heat of sun and labor in the fields. And in place of the imaginary child we are asked to substitute “A man/A tramp [who] comes laboring across the stubble/Like a mirage against that blank horizon.” By imagining a tramp, Pinsky preserves a protagonist in the vision who has few, if any, responsibilities, the lack of which is the common ground between the child and him: they both have only a marginal place in the communal–and essential–harvest; they both lack a purposiveness, a commitment to social need. The difference is, of course, that the tramp can be held accountable for his want of contribution, whereas the child, by reason of youth and inability, is exempt from such expectation. He or she may be answerable for certain chores, let us say, but typically is not fully capable of hard labor, and so is not fully liable for it.

To substitute an adult protagonist for the child is to explode the nostalgia for the idyllic transcendence and its attendant ethics. Not only does the poet lead us to qualify our pastoralism by admitting to the actualities–unrelenting heat, back-breaking labor, social uselessness or irrelevance–but he also leads us to question our commitment to an absolutist metaphysics that yearns for an escape from differences into certain goodness and knowledge. The cruelties of such an escape–its bodily and psychic violations–are obscured by the poetic locution in which the child’s transcendence is imaged: “The bubble of the child’s heart melts a little” into “the particles of the garden/0r the motion of the grass and air.”

But hearts are not bubbles, nor do they melt a little–or if they do, the spectacle is not an idyllic one. The physical form has a structural integrity apart from the metaphors it might suggest. Indeed, we are mistaken to treat metaphor otherwise than to observe the primary differences that it preserves between the things it compares. The relation between vehicle (heart) and tenor (bubble) is analogical, not one of apocalyptical sameness. It attests to the resemblances of attributes of the things, but does not assert the identity of the things themselves. So the figurations of metaphor cannot prove that the consequences of the child’s bubbling dissolution will be what the underlying metaphysics claim they will be: the peaceful melting of an individuated consciousness into the goodness and knowledge excluded by the self’s autonomy. We cannot be sure that the bursting of the heart, which ostensibly releases the self or soul contained within it, is commensurate with the bursting of the bubble, which releases into the general atmosphere the breath of air it envelopes.

Nor can those figurations prove what the imaginary poet– Pinsky’s third and final protagonist–wants to prove as he, too, introduces himself to the prairie and writes “a poem about a Dark or Shadow/That seemed to be both his, and the prairie’s–as if/The shadow proved that he was not a man,/But something that lived in quiet, like the grass.” This archetypical romantic is aligned with the childish dissolving of the self into the “motion of the grass and air.” But he cannot treat that shadow as real, not without first addressing the fallacy in his principle of identity, nor without taking into account the actual violence to the individual that his fallacy, as a spur to action, would entail. The only difference between the poet-child and the tramp is that the former treats his metaphysics as fiction: he writes “as if The shadow proved he was not a man.” The latter, however, treats them as real: he “climbs up on a thresher…and jumps head-first/Into the sucking mouth of the machine,/Where he is wedged and beat and cut to pieces.” The tramp’s realistic suicide bares the consequences of an ethics, a love of death, whose rhetoric has great power to persuade, without having the equal power to describe actual conditions and desirable ends.

Now, a pragmatic man, and not a child or poet, might feel himself immune to the grotesque seductions of “easeful death.” Certainly those farmers, who “shout and run in the chaff” upon seeing the tramp leap head-first into their thresher, are not titillated, but are horrified–and probably mystified as well. And yet they might unwittingly have a great deal in common with the tramp’s and the child’s and the poet’s love of death. For its cosmology, which presumes an elision of “sun and air” with “goodness/And knowledge,” lends itself to a religious extremity to which these same tough-minded farmers are liable to adhere. As Pinsky’s careful speculation reasons in “Bad Dreams” (An Explanation of America), they might once have been “Protestant, with a God/Whose hand was in every berry, insect, cloud:/Not in the Indian way, but as one hand /Immanent, above that berry and its name.”

Such immanence, if real, would deify the “obliterating strangeness and the spaces” of the empty prairie landscape, thereby positing in nature that otherwise uncertain goodness and knowledge, which would in turn sanctify the settlers’ civilizing customs as they were conditioned by the environment–as all agrarian communities are. Because its commerce would be thought to involve, therefore, a congruence of natural and spiritual facts, a settlement’s material prosperity–its harvests–would be a moral good as well. Its mores, inevitably contingent upon those harvests, would be godly, its civil law would be holy, and its power would be righteous. Such religious, political and economic architectures not only could ratify the virtue of its inhabiting citizens, but it could endorse as well the extermination of differing communities founded on other spiritual premises and thriving according to-other natural sciences. For those material differences would be ethical evils. Hence the moral approbation of the European, and later American, expansionism in the New World, and of the inexorable genocide of the indigenous peoples: “The ordinary passion to bring death/For gain and glory,” the poet explains, “would be augmented and inflamed/By the harsh passion of a settler; and so/Why wouldn’t he bring his death to Indians/Or Jews, or Greeks…?”

Pinsky’s conditional tenses, in which he phrases his “Bad Dream” of a mystic, death-loving civilization, are not meant to hedge his summary of a shameful American history, the circumstances of which he assumes are well-enough known in their general outline. Rather, he means by them to qualify his explanation of that history: an explanation granted on the terms of his “idea” of the country and its past, made to his “idea” of his daughter, and so recognizing all the limitations, philosophical biases, personal colorations and inevitable differences those “ideas” will entail. His account is an approximate one, necessarily, because “what I know,/What you know, and what your sister knows…/ All differ.” The perceived absence of congruity, the variations of individual experiences, the distinct acquaintances with fact, all separate the father from his daughters, as each daughter from each other, and so compel—in the name of intelligibility—a commitment to a process of education.

Unlike snakes, he writes in “Serpent Knowledge” (An Explanation of America), which “are born (or hatched) already knowing/Everything they will ever need to know”–and which, therefore, “Are not historical creatures”—unlike these snakes, people are “Not born already knowing all we need,/One generation differing from the next/In what it needs, and knows.” Unless, like those mystic settlers, we treat our differences as abhorrent abominations, we are compelled by our separations to discover what we have in common with each other. That discovery is infinite: “whatever happens/In actual New York, it is not final,” the poet admits, “But a mere episode…on some stage.” Consequently, we can never know all we need, but continually must revise our explanations and expectations according to the flux of novel circumstances; “Where nothing will stand still/Nothing can end–but recoils into the past,/Or is improvised into the dream or nightmare/ Romance of new beginnings.”

The hope, then, that he extends to his daughters–Hope which is “an authority transcending power/ Or even belief”–is not and cannot be for any particular history, any safety, or wisdom, or time, or place. Rather, he hopes for history itself, for its novelty that erases all accounts of it, and that compels us to envision new starts–to continue, in other words, to live

It Occurred To Me That…

I should call attention to the project that the potter Ehren Tool has been engaged in for some time now. He has a compelling, wonderful installation at the Renwick Museum in Washington D.C., entitled 198 of Thousands, which is a collection of his ‘War Cups’ (This is my phrase, and not what he has chosen to call them). Each is made of stoneware, various glazes and decals. He is himself a veteran of the Gulf War, and his cups initially reflected his personal experience, but have grown to encompass the struggles of other soldiers, and their families. Here are links to his website, and to a recent interview with him:

http://www.dirtycanteen.com/ehren-tool.html

http://inthemake.com/ehren-tool/

The cup in these photographs reflects the traumas of Cortes’ invasion of Mexico, and the conquest of the Aztec civilization—as imagined in the last two chapters of my book Genealogies, some lines of which appear below.

Crow-headed women picked through

the battlefields in a final rally within

the heat beneath the blue mountain clouds,

the mesas emptied. Sarah didn’t wait

for the awful flocks before she gathered

Elam from reconnaissance, and

together took positions like a mist

might insinuate onto a morning

beach—by which I mean, and by occult

degrees, they faded from perception as

they neared the city common. If they were phantoms,

they’d like to be assassin phantoms as

they hefted their munitions invisibly

into abandoned rooms upstairs in view

of the proceedings in the courtyard on

the well-made work of masons, where Cortes

negotiated with ambassadors from mercenary

nations, traded promises of plunder

with his higher math, using zeros,

and with no one looking stashed the novel

treaties in the toilet of his disrespect.

Thank you, I’ll take that. Elam reached

to Sarah for the firing pin, and springs,

and reassembled the dark machine of destiny,

is how Sarah thought of it: the rifle

oiled in Elam’s hands, and ready. Get

used to it. He levered in a cartridge

for the modest shot from there, and read

the white winds. The sacred sky was blazing

with a clarifying light, allowing

him to see an end, at last, of action as

he fired. The hammer detonated the

percussion cap exactly at the moment

when the mountains shook like green robes,

closing distant roads with rocks, scattering

scarlet flocks of parrots screeching up

through rising plumes of dust. Adobe buildings

swayed, or crumbled. The tremblor shocked the audience,

rocked Cortes off the dais. Several

celebrants heard a leaden insect

missing them. In the melee, Elam

levered in another round—no

man of mercy in this mood—braced

against a rolling seismic wave, and once

he sighted grimly on Cortes. He shot

for the umbilicus exposed below

the armored chest plate. That would stop

his exclamation, and by the way, disband

the rash, inconsiderate, fiery

voluntaries left from the invading

expedition.

Except, to begin with,

nothing happened as expected. It looked

as if the god of plagues had come

again because, before the slug could strike,

the body lice and European biome

bloomed on Cortes into a mythical

immune response protecting him from any

outside missile. The bullet simple shorted

out, with loud and visible effects.

Clouds of living powder flew in colorful

eruptions, lightning clapped about him with

its smoke and bounce, igniting little fires,

spores and alien bacteria

basically ate everything around him,

and left a circle of ancient visitation.

Whereas the implications wouldn’t register

with Elam, prodigious in testosterone,